In fond memory of D.C Fontana, who died yesterday at the age of 80, I am reposting this homage I wrote for the Mindful(l) Media podcast in 2015. She will be greatly missed. – Rosanne

As a child I didn’t come to Star Trek for the fantasy or for the fun futuristic optimism or even for the glory of the gadgetry of the tricorders and communicators. I came for William Shatner’s chest. Glimpsed quickly one day while changing channels, my pre-adolescent hormones screeched to a halt as I sat transfixed. That tight Star Fleet uniform shirt truly rippled across his chest, which seemed to strain to be released. We didn’t ‘flip’ in those pre-remote days. We sat in front of the set and manually spun the dial like the combination lock on our high school lockers, which brought us in to much closer contact with the (sometimes still black and white) pictures flashing upon our (compared to modern day frightfully small) screens. I don’t even remember which episode it was that first placed his pecs in front of me, but this obsession with Shatner’s chest focused me so much so that I never cared for the writers’ propensity for finding ways for his co-star to flaunt his own brand of sexuality. Forcing the unfeeling Mr. Spock to feel never moved me at all, so in second, third and fourth runs I never found “This Side of Paradise” much to my liking. In the epic mash up between Sexy Shatner and Sexy Spock, Shatner always won. But being a budding television writer even as a ten year old, I recognized in the idea the need to offer the actor a way out of the rigid character description enforced upon him by his creator.

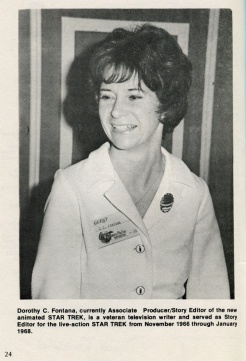

Viewed now from the perspective of a fifty-year old female television writer and scholar, no longer merely a fan, I find the episode fascinating for what it says about the history of women writers — and the female characters they create — in television. In those days of heady chest-worshipping I didn’t know that the D. C. in D. C. Fontana stood for Dorothy Catherine. When I later learned that information from reading The Making of Star Trek, I took her success as a beacon for my own journey, as did many other future female television writers I came to meet throughout my career. While countless books have been written about the influence of the program on science fiction and on television in general, what I came to learn was the influence Star Trek wielded on bringing women into the industry — and how their participation changes the way female characters are portrayed.

Viewed now from the perspective of a fifty-year old female television writer and scholar, no longer merely a fan, I find the episode fascinating for what it says about the history of women writers — and the female characters they create — in television. In those days of heady chest-worshipping I didn’t know that the D. C. in D. C. Fontana stood for Dorothy Catherine. When I later learned that information from reading The Making of Star Trek, I took her success as a beacon for my own journey, as did many other future female television writers I came to meet throughout my career. While countless books have been written about the influence of the program on science fiction and on television in general, what I came to learn was the influence Star Trek wielded on bringing women into the industry — and how their participation changes the way female characters are portrayed.

Because of Fontana, future writers of future Trek franchises invited other female writers to pitch ideas so that, to my great joy twenty years after I stumbled upon the original Trek, I found myself in the offices of Star Trek: The Next Generation pitching ideas for stories involving what was still largely a boys club of characters. Sure, they had accepted two women into their continuing cast — both in ‘soft’ occupations as ship’s counselor and medical doctor and still under the command of Captain Picard. But the franchise had proved a stepping stone for a variety of female writers I admired (including Jane Espenson and Melinda M. Snodgrass) and I was excited to be among them. I never sold a story to that iteration of the show, but I kept watching — and kept noticing — that written by women, female characters were (and sadly are still) often more developed (in ways other than their chest measurements).

In “Paradise” that is true of what actress Nichelle Nichols is given to do as our cast regular female, Lt. Nyota Uhura (whose first name I never knew until the writing of this essay) and what Jill Ireland is given to do as the guest character, Spock’s former girlfriend, Leila (who in the tradition of sex objects was never provided a last name). Normally confined to dialogue discussing ‘hailing frequencies’ and only seen taking orders from Captain Kirk, in “Paradise” Uhura commits mutiny against her captain. He has to state for the Captain’s log that, “Lt. Uhura has effectively sabotaged all communications.” While all the male starship members also commit mutiny, Uhura is given one-on-one screen time with the lead actor to do so. Likewise, while Leila seems at first to only be demonstrating that the most perfect, porcelain-faced blonde can even be sexy in overalls, she was also spouting Thoreau (as in Henry David) and his brand of 19th century Transcendentalist philosophy to Spock — and to the audience. For a show airing at the height of the hippie movement, Leila served as a mouthpiece for their dream of peaceful co-existence, one not yet shared by other generations. In several online interviews Fontana has chosen Leila as one of her favorite characters, so we know much of what Leila says comes from Fontana’s own philosophies.

Of course, in the end television was then (and still is now) a man’s world so Uhura’s and Leila’s interests are eventually subsumed by Kirk’s desire to prove, “Man stagnates if he has no ambition, no desire to be more than he is.” This philosophy discounts ‘woman’ as part of ‘man’ and makes the female-gendered idea of creating peace and happiness submissive to the more male dominant idea of success defined by changing the world around him. Why is a love of nature, as evidenced in Spock’s line: “I have seen a dragon… but I’ve never stopped to look at clouds before, or rainbows” less of an ambition for man? Even the American Founding Fathers cared more for the land and its beauty than these final frontier founders seem to do as they travel the galaxy. Why is the existence of this previous girlfriend and the chance to hear “I love you” from a formerly feeling-less alien male, less of an ambition of (wo)man?

Despite her straining to include her voice in this world, the male producer(s) still stamped their voice on the final product that became “This Side of Paradise”. Over the course of my career, I came to learn that Fontana shared that experience with many of the female writers who followed her, each one planting just enough seeds or dropping just enough breadcrumbs of her own opinion onto the fields of male creation for the rest of us ‘chick writers’ to follow. Where as a child I saw “This Side of Paradise” as an epic battle between sexy male leads, as an adult I see it as the continued battle for the hearts and minds of the audience waged by writers of different genders. It is a fight that several other sisters have carried on through the decades and one I’m willing to declare has been won by a relative newcomer to the scene, Shonda Rhimes. Through the creation of her own new frontier in Grey’s Anatomy, Rhimes provides male and female audiences alike with an all-inclusive world entirely conceived in a female mind. What do both the male and female doctors of Seattle Grace Hospital hope to provide their patients everyday? As Rodenberry provided a masculine ‘trek’ for man into the final frontier, the feminine goal Rhimes provides her characters is right there in the title of the hospital, ‘grace’. (And thanks to D. C. Fontana, Shonda chose to use her first name in her credits.)

Despite her straining to include her voice in this world, the male producer(s) still stamped their voice on the final product that became “This Side of Paradise”. Over the course of my career, I came to learn that Fontana shared that experience with many of the female writers who followed her, each one planting just enough seeds or dropping just enough breadcrumbs of her own opinion onto the fields of male creation for the rest of us ‘chick writers’ to follow. Where as a child I saw “This Side of Paradise” as an epic battle between sexy male leads, as an adult I see it as the continued battle for the hearts and minds of the audience waged by writers of different genders. It is a fight that several other sisters have carried on through the decades and one I’m willing to declare has been won by a relative newcomer to the scene, Shonda Rhimes. Through the creation of her own new frontier in Grey’s Anatomy, Rhimes provides male and female audiences alike with an all-inclusive world entirely conceived in a female mind. What do both the male and female doctors of Seattle Grace Hospital hope to provide their patients everyday? As Rodenberry provided a masculine ‘trek’ for man into the final frontier, the feminine goal Rhimes provides her characters is right there in the title of the hospital, ‘grace’. (And thanks to D. C. Fontana, Shonda chose to use her first name in her credits.)

All this musing makes me wonder how many young female writers are now coming to their careers because of a love of the way Patrick Dempsey’s chest ripples under his uniform shirt?